Ellen Craft in Disguise. Five Hundred Thousand Strokes for Freedom. London:

W. & F. Cash, 1853.

Our guest blogger today is Cottey College student Carmen Key. Thanks Carmen!

At eleven

years old, Ellen Craft was given as a “gift” to her half-sister in 1837. The

daughter of a biracial mother and a wealthy slave owner, Ellen’s fair-skin

ensured her an in-house servant position which made her privy to conversations

about the city she was in that would later help guide her to freedom. Moreover,

her light skin would be the power behind her idea to disguise herself as a

white male slave owner traveling with her slave (Ellen's husband, William) to

Pennsylvania for health reasons. Ellen had no choice in what family she would

be born into. She had no control over being born into slavery. However, Ellen

had barely left her teen years behind before she decided to take control of her

life even if it meant losing it.

At twenty

years old Ellen and her husband William decided that they would do what no one

had ever done. They would escape slavery not by the Underground Railroad or by

shipping themselves to a free state like Henry "Box" Brown. Ellen

decided that they would hide in plain sight. So, with her arm in a sling to

prevent the awkwardness of being asked to sign anything along the way (slaves

were not allowed to learn to read or write) and her face wrapped partially in

gauze to keep her accent a secret, Ellen and her husband, who was also a slave,

took the first step of their daring four-day escape to the North where they

could live free. They had nothing but their wits and the Good Lord to bring

them through and fortunately, that was enough!

Ellen

Craft and her husband William made it to the North and because of their great

escape, they quickly became famous to freemen and abolitionists alike. Their

journey to freedom was lauded as a sensational feat and within months they were

speaking at antislavery conventions and other abolitionist events. They shared

the stage with the likes of Frederick Douglass and Wendell Phillips. Often it

was William who spoke but it was Ellen who became the star. Their story was

widely reported in mainstream newspapers and the articles emphasized Ellen’s

primary role in the escape. One account reprinted as far away as Honolulu,

Hawaii, reported that “not once did Ellen’s courage fail, nor her inimitable

and unapproachable endurance and perseverance give way.” Abolitionist W.W.

Brown declared her “truly a heroine.”

The

British Friend 7 (March 1849): 65.

The Crafts

probably would have settled into Boston life; Ellen raising children and

working as a seamstress while her husband made furniture except for the passage

of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This law would require northerners to assist

southern slave owners to recapture runaways. Unfortunately, this meant that those

who had escaped to the North were no longer safe there and this, of course, included

Ellen and William. Soon agents arrived in Boston looking for the couple. In

fact the very first warrants issued under the new law were for the arrest of

the Crafts because they and their story were so famous. President Millard

Fillmore even threatened to send in the army to capture the pair. Newspapers

across the country reported on the episode, reminding everyone of their daring

escape from Georgia just two years ago.

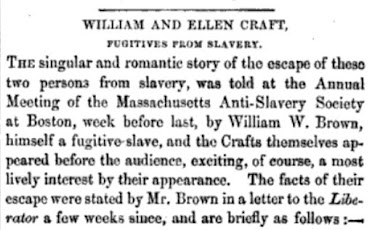

Ellen and William Craft. Liberator photo files.

Ellen wisely took refuge at famed abolitionist Reverend Theodore Parker’s home while her husband was kept safe at black activist, Lewis Hayden’s house. They were under heavy protection as not only were these homes guarded, but the owners threatened to respond with explosives before they would ever give up the Crafts. The abolitionists were able to harass the agents out of town, but Ellen knew she and her husband needed to leave. Soon after, they journeyed to London. Ellen Craft and her story were already known in England. She was invited to important events (such as a special viewing of Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition of 1851) and was visited by famous people. Newspapers in the U.S. covered these events and apparently that pushed someone to make up the story that Ellen was unhappy with her freedom. In the fall of 1852 editors across the South printed an article claiming that Ellen Craft was asking to return to the family she had escaped from. Ellen responded with a statement for the newspapers:

I write these

few lines merely to say that the statement is entirely unfounded, for I have

never had the slightest inclination whatever of returning to bondage; and God

forbid that I should ever be so false to liberty as to prefer slavery in its

stead. In fact, since my escape from slavery, I have gotten much better in

every respect than I could have possibly anticipated. Though, had it been to

the contrary, my feelings in regard to this would have been just the same, for

I had much rather starve in England, a free woman, than be a slave for the best

man that ever breathed upon the American continent.

--Anti-Slavery Advocate, December

1852

The Crafts

lived in Great Britain for nearly twenty years, raising their five children.

After the American Civil War, they returned to the U.S. educated and having

worked hard on behalf of abolitionism. They ultimately started a school

specifically for freed slaves in Georgia, which was their home state. Ellen had

made her escape to return and prepare other freed slaves for life with no

boundaries. Ellen died in 1891 and William in 1900.

Even today Ellen Craft remains a celebrity. Deadline reports that a Hollywood movie is in the works. Ellen’s fans reach far and wide as her roots in the South, escape to the North, and years overseas garnered her undisputed fame in many places. William and Ellen authored a book about their journey, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, though it was published under his name only. Historians have concluded that Ellen contributed and the book is now attributed to them both. After all, Ellen was the true heroine of the story.

Sources and Further Reading

“Boston Minister Tried for

Inciting Riot” MassMoments. https://www.massmoments.org/moment-details/boston-minister-tried-for-inciting-a-riot.html

Brusky, Sarah. “Ellen Craft”

Voices from the Gap. 2009. https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/166136/Craft%2c%20Ellen.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Craft, William [and Ellen]. Running

a Thousand Miles for Freedom: Or, The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from

Slavery. London: William Tweedie, 1860. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Running_a_Thousand_Miles_for_Freedom/C50TAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

McCaskill, Barbara. “Ellen Craft: The Fugitive Who Fled as a Planter.”

In Georgia Women: Their Lives and Times, edited

by Ann Short Chirhart and Betty Wood, 82-105. Athens: University of Georgia

Press, 2009.

“Story of Ellen Crafts.” Polynesian

[Honolulu, HI], October 27, 1849. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015408/1849-10-27/ed-1/seq-4/#date1=1849&index=7&rows=20&searchType=advanced&language=&sequence=0&words=CRAFTS+ELLEN&proxdistance=5&date2=1849&ortext=&proxtext=&phrasetext=%22Ellen+Craft%22&andtext=&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1

“William and Ellen Craft: Fugitives from Slavery.” The British Friend 7 (March 1849): 65-66. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_British_Friend/YgUFAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22ellen+craft%22&pg=RA1-PA65&printsec=frontcover

“William and Ellen Smith Craft Photo Album.” Avery Research Center at

the College of Charleston. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:39896?tify={%22panX%22:0.541,%22panY%22:0.616,%22view%22:%22info%22,%22zoom%22:0.495}

No comments:

Post a Comment