Detail of Afong Moy (1815@ to ?). The Chinese

Lady

Courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections

When Afong Moy appeared in Providence, Rhode

Island, in 1835, the local newspaper encouraged all to go see the first female

visitor to the United States from China. The editor argued the Chinese Lady

served as a “living specimen” of a culture known of but not truly experienced. Children

learned of the many dynasties in school. Americans drank Chinese tea and possessed

a considerable number of goods from China: fans, combs, shawls, baskets, games,

porcelain, and silks. Women learned from magazines how to dress and style their

hair in the Chinese fashion. Few Americans, however, had traveled to Asia or

had encountered anyone from the region. The Providence newspaper pointed out

that this event was a perfect chance for many to learn about the customs of a

culture “which is so different from anything with which they have been

acquainted.”

Rural

Repository (Hudson, NY) February 28, 1835, 159

Americans learned about China from Afong Moy and

in turn made her a celebrity. They attended her performances in large numbers

wherever she traveled, paying twenty-five to fifty cents each. Fans pasted

newspaper reports in their diaries and commented on their experiences. Teen-aged

Margaret Gibson sympathized with Afong Moy in her letter to her brother. She

wrote “Poor thing she is much to be pitied, she seemed

very timid, and confused.” A Baltimore woman dressed as her for a

masquerade ball. Race horse breeders named fillies after her. Men wrote poems

in her honor; William Tappan of Cincinnati published one that began “I marvel

at thy curious mien, thy strange, fantastic air.” Newspapers widely reported

on her tour and spread rumors of her marriage prospects, her alleged disappearance,

and the likelihood of her publishing a journal of her travels.

And those travels were extensive. Afong Moy

arrived from China in 1834 when she was about nineteen, accompanied by a maid

and an American female chaperone. Historians know little of her background or

even her true name, but she was likely the daughter of a merchant in the city

of Guangzhou. American traders arranged her passage across the ocean and her

presentation to audiences in the United States as a promotion for the goods

they were selling. They created a setting filled with Chinese art and furniture

where she could (with help from an interpreter) share elements of her culture

such as dress, song, her bound feet, and eating with chopsticks.

Afong Moy apparently believed she would be returned

to her home after one year. She appeared before audiences in New York,

Philadelphia, Washington, DC (where she met President Andrew Jackson),

Baltimore, Charleston, Boston, Providence, and many smaller communities

throughout New England. She experienced a grueling schedule but rather than

travel back to China after a year, she continued on the road with an

entertainment manager, covering one thousand miles in 1836. She performed,

along with musicians and magicians, in Florida, Cuba, New Orleans, and towns

all up the Mississippi River before returning to audiences in New York City. Afong

Moy saw more of America than most of its citizens. Unfortunately she never

published a journal and we know nothing of her perspective.

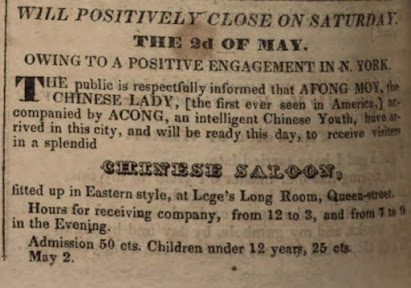

Advertisement in Southern Rose Bud (Charleston, SC) May 2, 1835, 144

She could have used the royalties from a book

since, though a star, she was not wealthy. When audience numbers declined in

1837, she found herself hobbled by her bound feet and alone in a New Jersey poorhouse.

Those who had taken care of her were gone: her maid, chaperone, manager, and

interpreter. Outraged fans publicized her plight and newspapers across the

country printed demands that she be helped to return to China. She received

much needed money but no opportunity to go home.

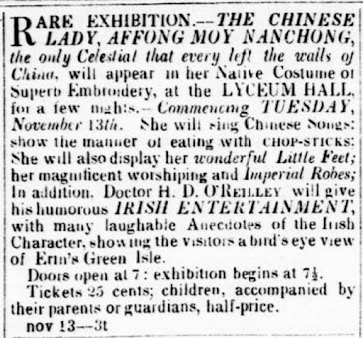

Alexandria Gazette, November 13, 1849

P.T. Barnum revived her career in 1847 when

Americans had a renewed interest in everything Chinese but he replaced her with

a younger woman from China by 1850. In 1851 Afong Moy performed in Cleveland,

but it is unknown what happened to her after that. She remained the first

Chinese woman in America but others had followed. She died in obscurity but not

as a specimen.

Sources

Davis,

Nancy E. The Chinese Lady: Afong May in

Early America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

“Extraordinary

Arrival—The Young Chinese Lady.” Alexandria

Gazette October 21, 1834. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1834-10-21/ed-1/seq-2/#date1=1789&index=0&rows=20&searchType=advanced&language=&sequence=0&words=Foo-chee+Julia&proxdistance=5&date2=1963&ortext=&proxtext=&phrasetext=julia+foochee&andtext=&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1

“Margaret

S. Gibson to John Gibson” Maryland Historical Society, quoted in Davis, Chinese Lady, 158-159.

Haddad,

John. “The Chinese Lady and China for the Ladies: Race, Gender, and Public

Exhibition in Jacksonian America.” https://www.chsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/2011HP_02_Haddad.pdf

Republican Herald (Providence,

RI) Sept. 2, 1835, quoted in Davis, Chinese

Lady, 182.

Tappan,

William. The Poems of William B. Tappan. Philadelphia:

Henry Perkins, 1836. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t4hm5sm1q&view=1up&seq=5

Thanks

for reading! Have a question or comment? Let me know!

To subscribe, email angela.firkus@gmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment