Evelyn Nesbit, 1900. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-12056

Evelyn Nesbit willingly shared her face with the

world at the turn of the Twentieth Century. As a supermodel, she graced

magazine covers and promoted products from soap to sewing machines. When her

husband killed the man who raped her, she reluctantly shared her story with the

world to defend his action. Nesbit felt this exposure much more acutely than

she had previous publicity. Journalist Nixola Greeley-Smith labeled Nesbit the

“frail cause of the tragedy.”

Burr-McIntosh

Monthly (Feb. 1905).

Nesbit posed for hundreds of photographs and

portraits before she reached the age of eighteen. Fans purchased her image on postcards,

in magazine spreads, and on canvas; paintings were displayed at the

Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Artist Charles Dana Gibson used

Nesbit as the model for his Eternal Question woman and the larger Gibson Girl

look it embodied. Lucy Maud Montgomery pinned Nesbit’s photo to her wall and

based her famous character Anne of Green Gables on the image. Advertisers

printed her face on beer trays, fans, tobacco cards, and calendars. Admirers

sent her love letters, flowers, and money. Millionaires proposed and finally in

1905 she married Harry Thaw, heir to a coal fortune.

Woman:

The Eternal Question by Charles Dana Gibson, 1901.

Nesbit abandoned modeling and her fledgling stage

career when she wed, but her husband dragged her into the public eye more than

ever before. Nesbit confided to Thaw before they married that she had been

raped when she was 16. Thaw went through with the wedding and in 1906 murdered

the villain, famous architect Stanford White, in front of hundreds of people.

Nesbit testified in court about the rape to further Thaw’s legal defense that

he killed White to avenge his wife’s honor. She also endured a multi-day cross

examination by the prosecuting attorney, who was determined to expose her as

immoral and unworthy of such a chivalrous act partly because Nesbit had

continued a relationship with White even after he drugged and assaulted her.

She also testified about White’s decadence, including free-flowing champagne, a

red velvet swing, and a bedroom with mirrors covering the walls and ceiling.

She said the court experience made her feel “stripped and naked and

defenseless.”

Tonopah

(NV)

Bonanza, Feb. 9, 1907.

Everyone obsessed about the murder and trial, with

Nesbit as the central character. Edison Studio released Rooftop Murder a week after the event and other filmmakers

followed. New Yorkers tried to push their way into the courtroom and rushed

Nesbit when she emerged from testifying. Elizabeth Schwenning, seventeen-year

old from Pennsylvania, apparently “lost her mind sympathizing” with Nesbit and ran

away from home to try to reach her in New York. Hawkers offered for sale Nesbit

postcards and even little red velvet swings. Businesses grabbed attention by using

her name and in the example below, contrasting Nesbit with their customers.

Salt

Lake (UT) Herald, Feb.

8, 1907.

Musicians published sheet music for songs dedicated

to her with titles such as “Nesbit Waltz” and “Sprinkle Me with Kisses,”

publishing her photo on the cover. Authors rushed books into print. Poet Judd

Mortimer Lewis wrote a poem that predicted that the jury would acquit Thaw

because of Nesbit’s beauty. “Oh, Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, while lawyers jaw and jaw,

and while they rant and saw the air, the jury sees that you are fair.” He

concluded with “Thaw sits there, but they don’t see him, you are the whole

entrancing show. And—as he’s yours—they’ll let him go.”

Times

Dispatch (Richmond, VI),

Jan. 28, 1907.

Newspapers across the country printed Nesbit’s

testimony verbatim. Americans could now not only look on the beautiful face of

Nesbit but debate, evaluate, sympathize, criticize, and speculate on her life

and character. Charles Hughes, editor of the Alienist and Neurologist, argued that Nesbit lied on the witness

stand since a woman never tells the truth about her “erotic life and relations”

and because she had good reason to do so, namely to save her husband from

execution. Congregational Minister Frank Smith however found, for an article in

the Advance, that those operating

barbershops, drugstores, and other gathering places in Chicago heard a nearly

unanimous public voice that believed Nesbit’s story. Some writers used the

occasion of the trial to publicize the fate of many youth seduced or assaulted.

Many others blamed Nesbit’s widowed mother for failing to protect her and for exposing

her to the life of a model and actress.

Evelyn Nesbit, 1913. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ggbain-13972

Nesbit, in contrast, never seemed to blame her

mother. She published her story in 1914 and admitted that becoming so famous at

a very young age was probably harmful. Nesbit found herself shunning the

“commonplace—a leisure that is entirely for those folk who get a good amount of

placid joy in finding things as they expect them, and expect very little.” She argued,

however, that she posed and acted simply for the money her family desperately

needed and realized that “freakish notoriety was not desirable from any point

of view.” Nesbit kindled her celebrity for decades with this mixture of disdain

for publicity and need for excitement as well as money (in 1915 she divorced

Thaw, who was found not guilty due to insanity). She acted on stage and in

films, danced, operated a tea room, created pottery, and wrote another memoir. Nesbit

remained best known however as the girl on the red velvet swing who caused one

man to die and another to go insane.

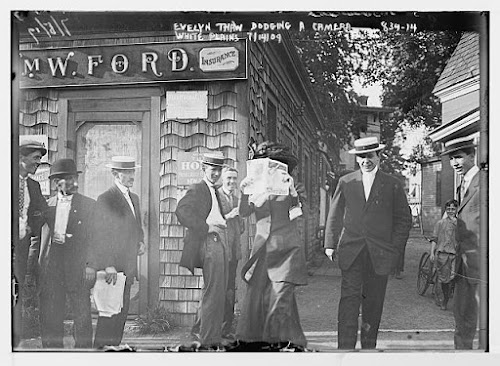

“Evelyn Thaw Dodging a Camera, White Plains” Library

of Congress, LC-DIG-ggbain-04049

Thanks for reading! Have a question or comment?

Let me know. Find links to previous posts above to the right and comment below. To subscribe, email angela.firkus@gmail.com

Sources and Further Exploration

Atwell,

Benjamin H. The Great Harry Thaw Case or

A Woman’s Sacrifice. Chicago: Laird and Lee, 1907. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nnc2.ark:/13960/t5hb10d01&view=1up&seq=9

“Editorial.”

Alienist and Neurologist 28 (Nov.

1907): 510. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Alienist_and_Neurologist/ni1YAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22evelyn+nesbit%22&pg=PA245&printsec=frontcover

“Evelyn

Nesbit Thaw on the Stand.” Fargo (ND)

Forum and Daily Republican, Feb. 7,

1907. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85042224/1907-02-07/ed-1/seq-1/#date1=1907&sort=date&date2=1907&searchType=advanced&language=&sequence=0&index=16&words=Evelyn+Nesbit&proxdistance=5&rows=20&ortext=&proxtext=&phrasetext=evelyn+nesbit&andtext=&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=13

“Girl

Crazed by Reading about the Thaw Trial.” Times

Dispatch (Richmond, VI), Feb. 22, 1907. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85038615/1907-02-22/ed-1/seq-2/#date1=1907&sort=date&date2=1907&searchType=advanced&language=&sequence=0&index=6&words=Evelyn+Nesbit&proxdistance=5&rows=20&ortext=&proxtext=&phrasetext=evelyn+nesbit&andtext=&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=41

Greeley-Smith,

Nixola. “Thaw and his Family Scrutinize Faces of Jurors, Looking for a Sign of

Hope, As Lawyer Delmas Pleads for his Life.” Evening World (NY), April 9, 1907. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030193/1907-04-09/ed-1/seq-3/#date1=1907&sort=date&date2=1907&searchType=advanced&language=&sequence=0&index=5&words=GreeleySmith+Nixola&proxdistance=5&rows=20&ortext=&proxtext=&phrasetext=nixola+greeley-smith&andtext=&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1

Lewis,

Judd Mortimer. “The Blind Goddess.” Cairo

(IL) Bulletin, Feb. 27, 1907. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn93055779/1907-02-20/ed-1/seq-2/#date1=1907&sort=date&date2=1907&searchType=advanced&language=&sequence=0&index=11&words=Evelyn+Nesbit&proxdistance=5&rows=20&ortext=&proxtext=&phrasetext=evelyn+nesbit&andtext=&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=36

Thaw,

Evelyn Nesbit. The Story of My Life.

London: J. Long, 1914.

Uruburu,

Paula. American Eve: Evelyn Nesbit,

Stanford White, the Birth of the “It” Girl, and the Crime of the Century. New

York: Penguin Books, 2008.

Williams,

Samuel. “Reporting the Great Murder Trial.” Pearson’s

Magazine 17 (April 1907): 455-462. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Pearson_s_Magazine/4rIRAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22evelyn+nesbit%22&pg=PA462&printsec=frontcover